SCULPTURE AGAINST THE GRAIN OF SPECTACLE

Alberto Giacometti e Rui Chafes: gris, vide, cris, curated by Helena de Freitas, on display at the Calouse Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon until September 18th, 2023, makes us reflect on the contemporary placing of sculpture, on the dialogue between works that come from different historical contexts and on the affective hue which is born from the silence of shapes.

During the time when I was a curator in MAM-Rio, I was lucky enough to be close to works by these two artists in two separate exhibitions, both in the monumental salon of the museum. In Alberto Giacometti’s (1901-1966) exhibition, curated by Véronique Wiesinger, which took place in 2012, the decision was to work with the vertical axis of the museum’s space, starting from the ground floor, passing through the monumental salon and ending in the mezzanine. In dealing with an artwork that fought to keep the human figure as vertical as possible, this axis was chosen as to explore the clash with the concrete walls, the scale tensions inherent to the monumental salon and the drifting appeal of the subjects that wandered helplessly through the space.

The exhibition of works by Portuguese sculptor Rui Chafes (1966), Carne Misteriosa [Mysterious Flesh], curated by Marcio Doctors, happened in 2013, the following year. There, the option was to reduce the scale of the monumental salon, enclosing within it a box in which the artist’s pieces could be displayed in a more contained, intimate setting. Between the last generation of modern sculpture, represented by Giacometti’s work, and Rui Chafes’ generation (formed in the 1980-90s), sculpture must face challenges such as the Pop hangover, exacerbation of virtual imagery and mediatic dilution of subjectivity. The public dimension of the sculptural experience has been lost, that is, the exemplary clash between plastic form and space which is presumed common, belonging to all and no one.

The current exhibition, this dialogue between sculptures, aims to set-on-stage a certain contemporary discomfort with the excess of visibility and the vertigo inherent to an accelerated displacement through the world (both physic and virtual). In a world where things cannot sustain themselves, in which everything circulates and is consumed, there isn’t much time to stop, much less to notice what is happening around us. How can we assume the currentness of sculpture, the medium of gravity and resistance by design, if everything seems to dissolve in the blink of an eye? What can sculpture accomplish today?

In a 1996 work titled “Sculpture: Publicity and the poverty of experience”, theorist Benjamin Buchloh faces the issues above keeping in mind a reality marked by “privatization of subjectivity and the fetishization of object experience”. Buchloh understands Giacometti’s work as the tragic last breath of a modernity that still believed in interdependence between subjectivity and the public sphere. Tense contractions of figures, drastic reductions in scale, aimless movement, curling bronze surfaces, all of that pointed to an attempt to answer to the loss of a way of experiencing the world, ruthlessly shattered by a barbaric World War II.

In this aspect, Giacometti’s work, such as Beckett’s, casts light on the desperate ending of a belief in the affirmative relation between language, subjectivity and the sharing of meaning. The fragmentation of the experience evoked by a superlative specialization of knowledge, plus the individuation of desire mobilized by advertisement and consumerism, impose a radical refigurement to the meaning of sculpture. As Buchloh points out, it’s not by chance that sculpture begins working with residues, with the agglomeration of scraps of daily life, with the unstructured fragmentation of form and cumulative seriality of industrial material. Pop, arte povera, minimalism and postminimalism are examples of these procedures. A most affirmative displacement would come from the transition from sculpture to site-specific with Morris and Serra. Focusing on the space instead of the object, these works can be articulated, by friction, with architectural, institutional and commercial externalities.

Therefore, it makes sense to engage Chafes and Giacometti in dialogue through the audaciously dry interventions in their work’s space of experience. Part of Chafes’ work comes from the creation of scenic-sculptural devices to deal with Giacometti’s pieces. Austere devices above all. A setting of vertigo inherent to the sculptural experience of the Swiss artist in the terms of Chafes’ poetics. It is unusual to find an artist working the exhibition space in such an incisive way without making it seem artificial or scenographic (in a bad way). The exhibition space was recomposed by the very sculptural experience that inhabited it – granting the space austerity, opacity and gravity. Affective hues that go against the grain of the spectacle and consumerism culture’s sensory appeal.

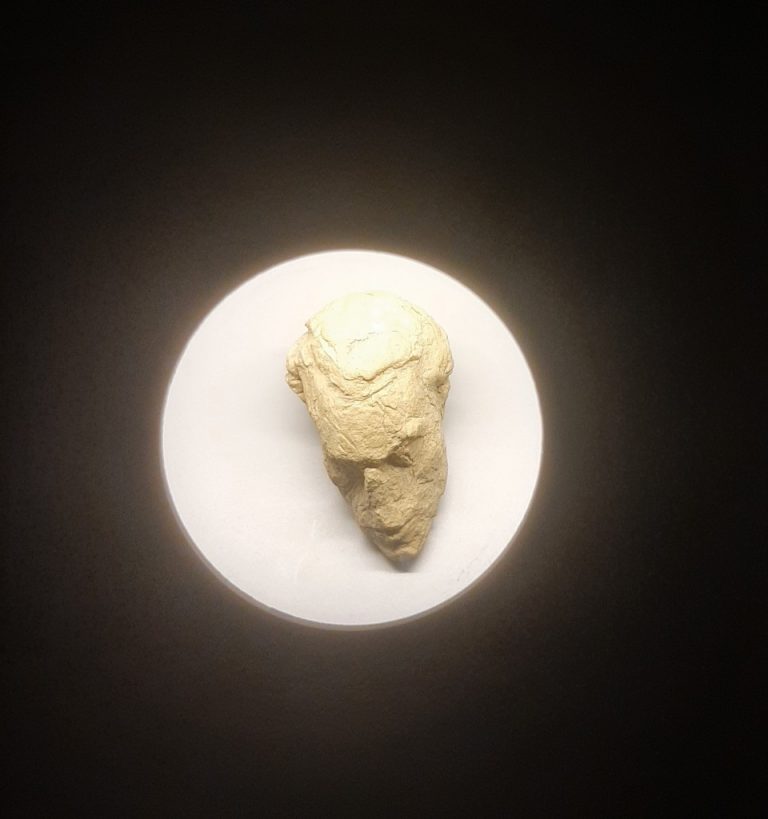

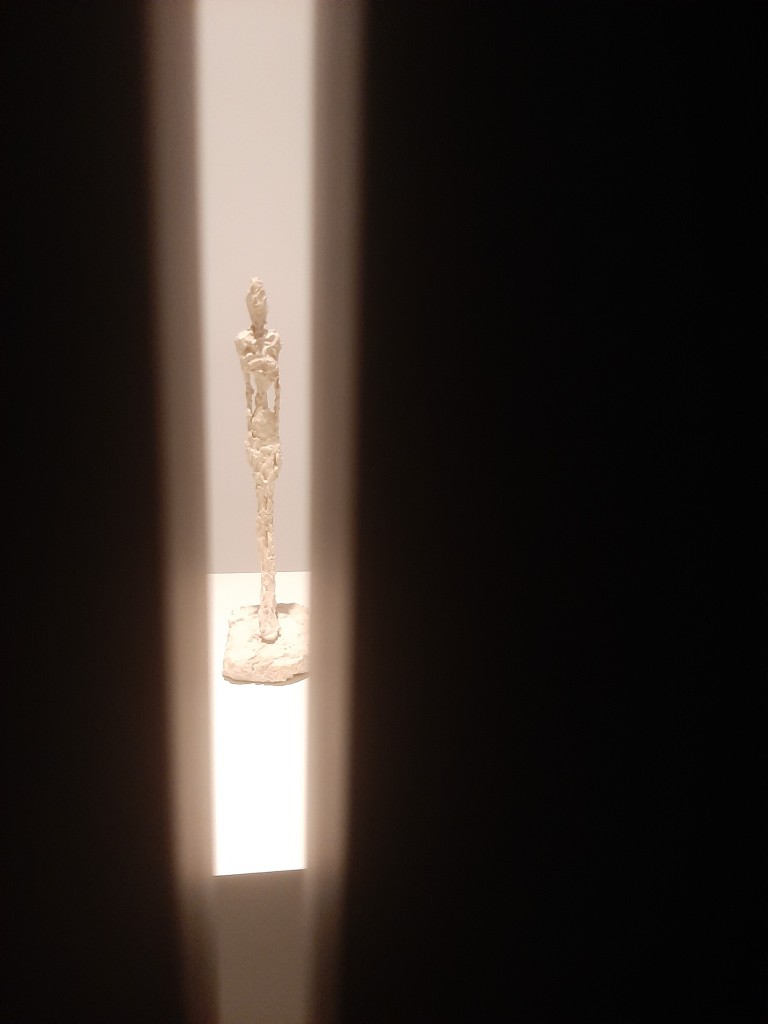

As we enter the exhibition, we are invited to pass through an iron cave built by Chafes. Initially, we are blinded. In complete darkness. Then a light appears, a hole and a small plaster head by Giacometti. By its side, small, lit vertical cracks in the iron walls, where slender figures loom. I recall one of the most stunning experiences I had during the setting of MAM’s Giacometti exhibition being the opening of transportation boxes, from which appeared Giacometti’s “resurrected” sculptures. In their frail and powerful verticality, they seemed to indicate that we can resist frivolity. Here, at Gulbenkian, these pieces rise from the interior of this black box, often hidden, glimpsed at through cracks in the walls, evidencing the difference between showing and displaying. There are invisible folds that feed the desire to see.

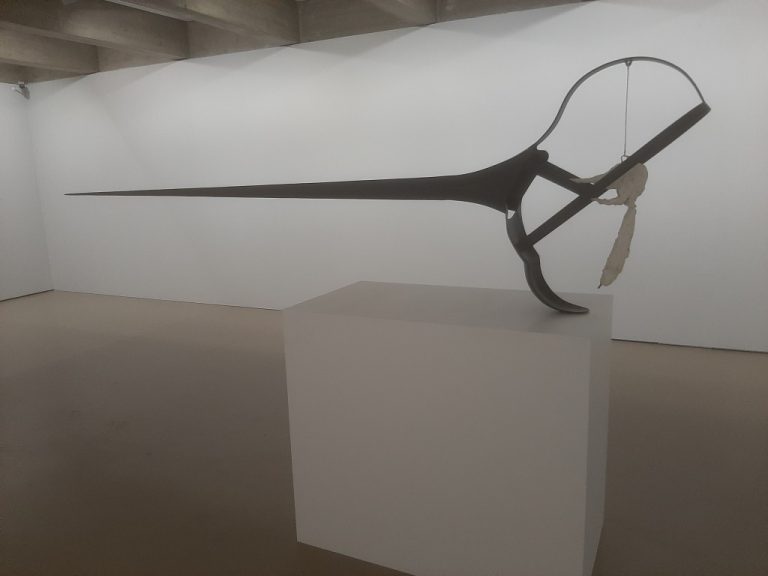

After passing through the iron cave, in which we are braked from the haste to look at an artwork and move on, we enter a sequence of small rooms, where a more direct dialogue between pieces by each of the artists is established. The atmosphere remains austere. White walls, beams of exposed concrete, indirect lighting. Chafes’ iron sculptures are irregular and hollow in volume. They are fragments of an inexistent body, insinuated by its verticality and the sensuality of the relation between big and small, interior and exterior. Inside the first room, the dialogue almost turns into a coupling as “La Nuit”, a pointed sculpture by Chafes, created for this exhibition and with that specific relationship in mind, welcomes in its interior an unfinished hanging plaster reproduction of a huge Giacometti nose. Two pieces that are integrated without being mixed.

While in Giacometti there is a drastic cutback in sculptural craftmanship as traditional bronze materiality and figure residue is sustained, in Chafes the thorough sculptural work resurfaces in the handling of iron and welding and in the suggestive fragmentation of the body. Barnett Newman referred to Giacometti’s sculptures as if their matter, bronze, had been chewed and spit out. With Chafes everything is worked up to the details. One focuses its work on the curly surface of the figure, and the other in the creation of entrails in flat and opaque iron plates. One experiments sculpturally with the erasing of a certain idea of body and humanity, and the other works in constructing a posthuman figuration, an erotic symbiosis of organic and inorganic shapes.

We pass through four small rooms punctuated by a dialogue between iron and bronze, dissolution and reinvention of the body. Most of this dialogue is suggestive, with shapes metamorphosing. One of Chafes’ pieces sticks to the corner of a wall as if it jumped from its pedestal and landed on the wall. It’s unusual to see an exhibition which doesn’t scatter explanatory texts through its rooms. Nothing against the texts – they certainly fulfill their educational role, bringing the public closer to the curatorial narrative and cultural and historical context of the displayed works. However, being left free to establish a direct contact with the works, in this case, is simultaneously an enriching and unsettling experience. It’s as if we don’t know how to deal with emptiness anymore, with more silent and slow ways of “speaking”. In the decision to not display texts on the works, there is a political refusal of the educational-exhibition and the spectacle-exhibition. May each viewer respond to this dialogue between sculptures with their own tools, and not be startled by the silence. The scream in the exhibition’s title (cris) is there, but it’s silent.

By the end of the exhibition there is another iron sculptural volume, built by Chafes in order to contain, within it, a small, minuscule sculpture by Giacometti. This volume, however, is irregular – it is unbalanced in its space. Walking into it means losing the axis of movement, feeling its ingrained vertigo and facing a human figure centralized in its far end which maintains its perfect balance. By unbalancing us, Chafes faces us with a conscience regarding the body and its central role in the relation between what we feel, how we are affected and produce meaning from it. This unbalance translates much of the phenomenological experience of Giacometti’s sculptures. It’s as if he unbalances the direct relationship between size and scale: the more a figure is decreased, the bigger it becomes in our perception. The drawings are yet another example of this scale disorientation.

This exhibition shows us that blinding and unbalancing are ways to resist de acceleration flow, offering our perception a moment to deal with the emptiness, the gray and the silent scream of shapes that impose themselves on the world despite and against the desperate desire for consumption.

–

The images were taken by Luiz Camillo Osorio during his visit at the exhibition.